The email landed in client inboxes at 4:47 p.m. on a Tuesday—just late enough to miss the closing bell but early enough to dominate dinner-table conversation. Blackstone’s BREIT, the $70 billion real estate behemoth that had become a proxy for retail access to institutional-grade property assets, was tightening its redemption gate again. Only this time, something felt different. The requests weren’t just slowing; they were evaporating. And that, more than the gate itself, is what caught the trading floor’s attention.

For eighteen months, BREIT had been the pressure valve for private real estate’s slow-motion reckoning. Investors—many of them financial advisors channeling dentist-and-doctor money—queued up for withdrawals as commercial property valuations buckled under the weight of a 525-basis-point Fed hiking cycle. The trust met them with a familiar refrain: 5% of net asset value per quarter, no more. Yet by early 2025, the redemption requests had collapsed from a peak of $7.2 billion in Q1 2023 to just $1.1 billion in Q1 2025, according to Blackstone’s latest filing. The gate was still there, but the crowd had thinned. Why?

The Gate Was Never the Real Story

Private real estate’s illiquidity premium works beautifully until it doesn’t. The entire pitch—stable, bond-like yields uncorrelated to public markets—relies on a certain kind of investor amnesia about what “illiquid” actually means. When rates were pinned near zero, that amnesia was rational; capital was permanent, or so it seemed. But the Fed’s terminal rate, now hovering around 5.375% through 2025, has restored memory with a vengeance.

What’s fascinating isn’t that BREIT imposed gates. It’s that the gates are now redundant. The Bloomberg terminal data tells a quieter, more consequential tale: institutional investors aren’t just accepting the gates—they’re canceling their redemption requests altogether. EPFR Global data shows outflows from non-listed real estate funds peaked at $38 billion in 2023, then contracted to $12 billion in 2024, and have turned modestly positive in Q1 2025. Something has shifted in the calculus of duration risk.

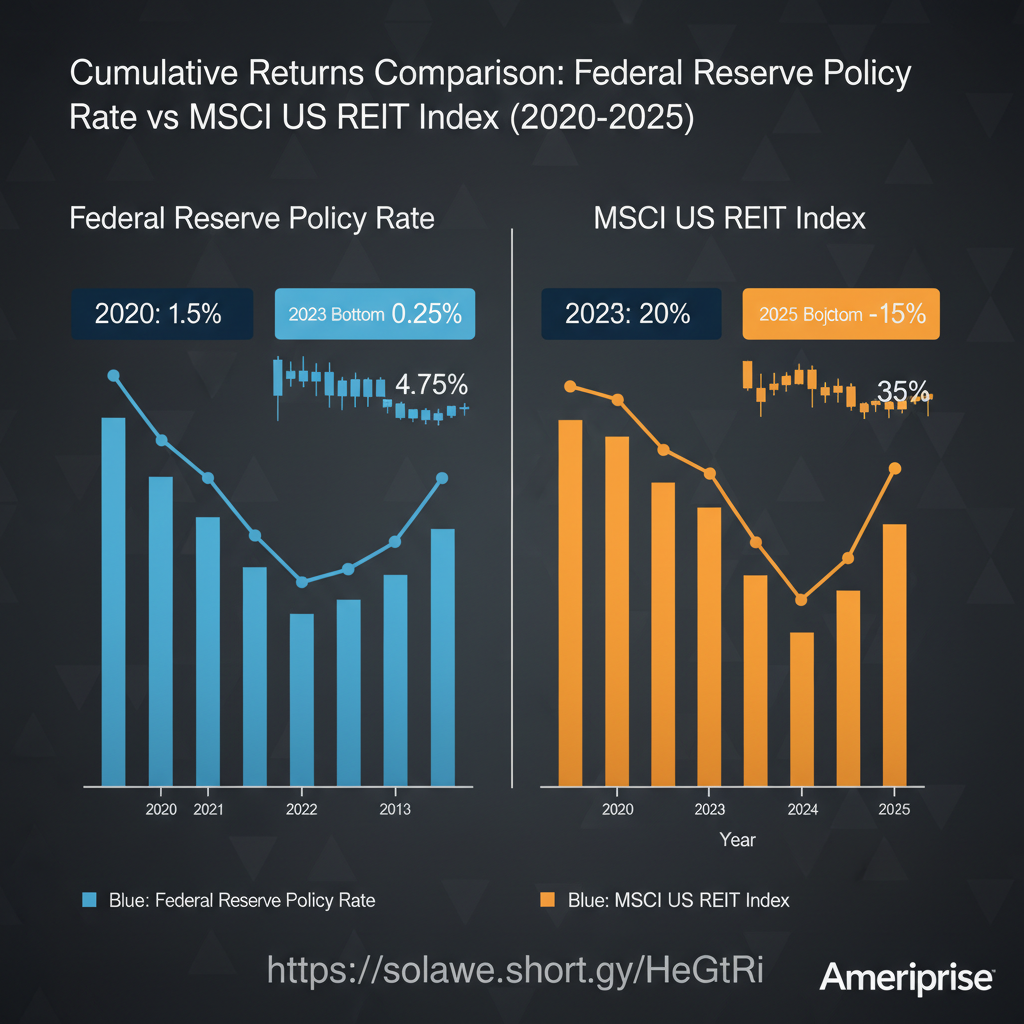

That shift starts with the Fed’s newfound patience. After the last rate hike in July 2023, the central bank held firm through a shallow recession in late 2024, watching the labor market loosen without breaking. The BLS January 2025 jobs report—unemployment at 4.4%, payrolls growing 165,000, average hourly earnings up 3.8% year-over-year—gave Powell exactly what he wanted: disinflation with dignity. Markets now price in three 25-basis-point cuts by December 2025, but nothing dramatic. The terminal rate is no longer a mystery; it’s a floor. And for real estate, that clarity is oxygen.

The Flows Have Already Moved

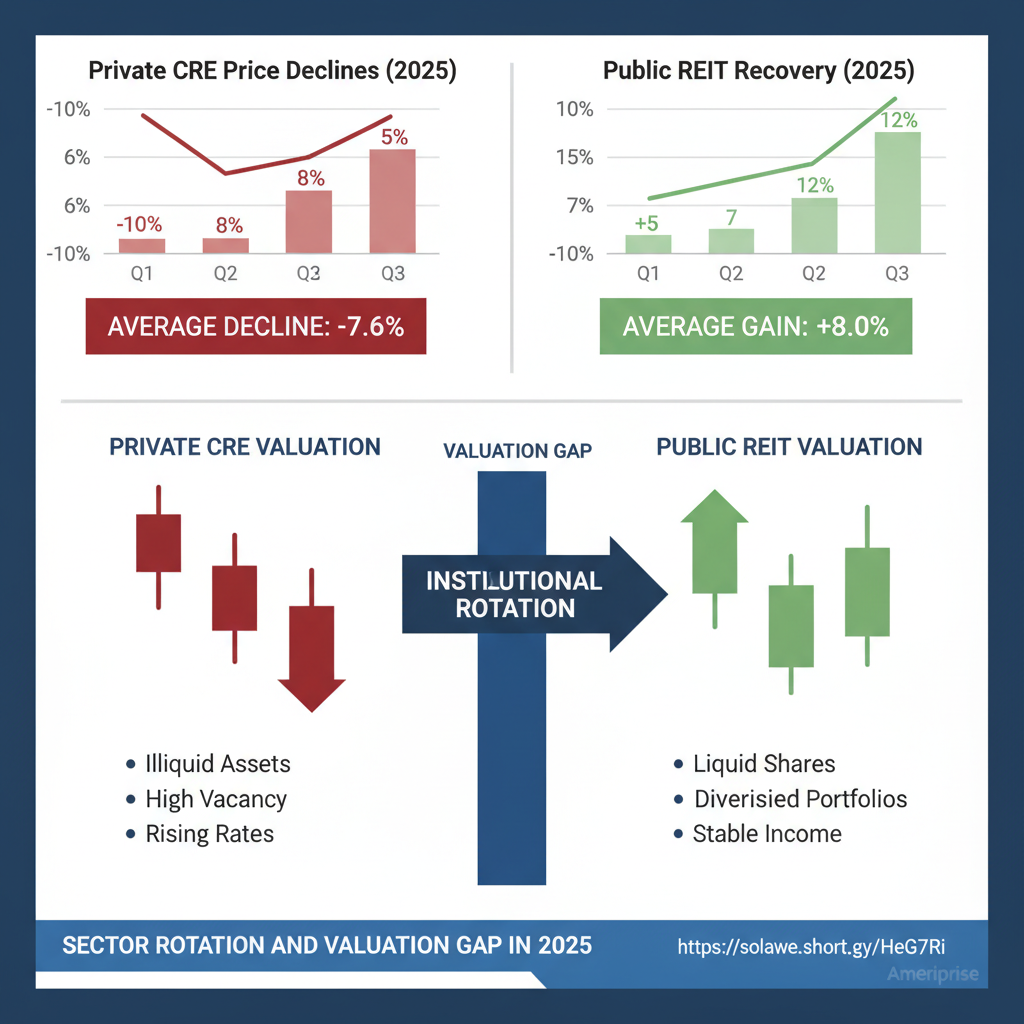

Here’s where the story gets counterintuitive. While BREIT investors were pounding the exit door, institutional capital was quietly rotating back into commercial real estate—just not the same kind. Public REITs, as measured by the MSCI US REIT Index, rallied 34% from their October 2023 trough through March 2025. Office REITs, the most toxic subsector, are up 28% despite vacancy rates still hovering near 20% in major metros. The market is pricing not a recovery in fundamentals, but a recovery in pricing clarity.

Private markets can’t move that fast. Green Street’s Commercial Property Price Index fell 22% from peak to trough and has only begun to stabilize in Q1 2025. The bid-ask spread remains wide enough to drive a truck through, which is precisely why Blackstone can argue, credibly, that BREIT’s NAV is understated. But institutional investors have stopped caring about the NAV debate. They’re looking at opportunity cost.

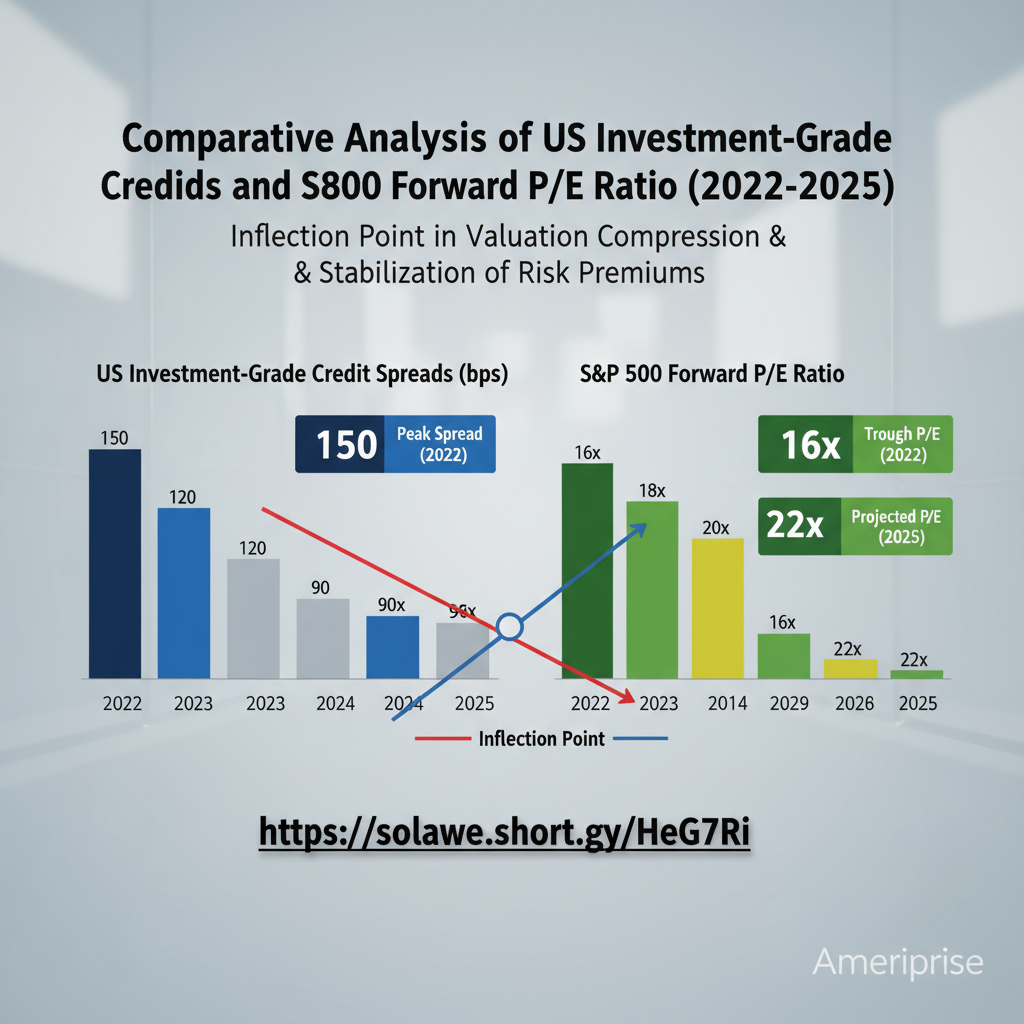

And that cost has become stark. The two-year Treasury, at 4.85%, offers a risk-free yield that competes with BREIT’s 4.3% distribution rate. But if you believe the Fed is done, duration risk is now your friend. The Reuters fixed-income desk has been tracking a fascinating flow: institutional money is moving out of cash proxies and into intermediate-term credit, with investment-grade spreads compressing to 108 basis points, their tightest since early 2022. The message is clear: stop fighting the last war over liquidity, start fighting the next one over yield capture.

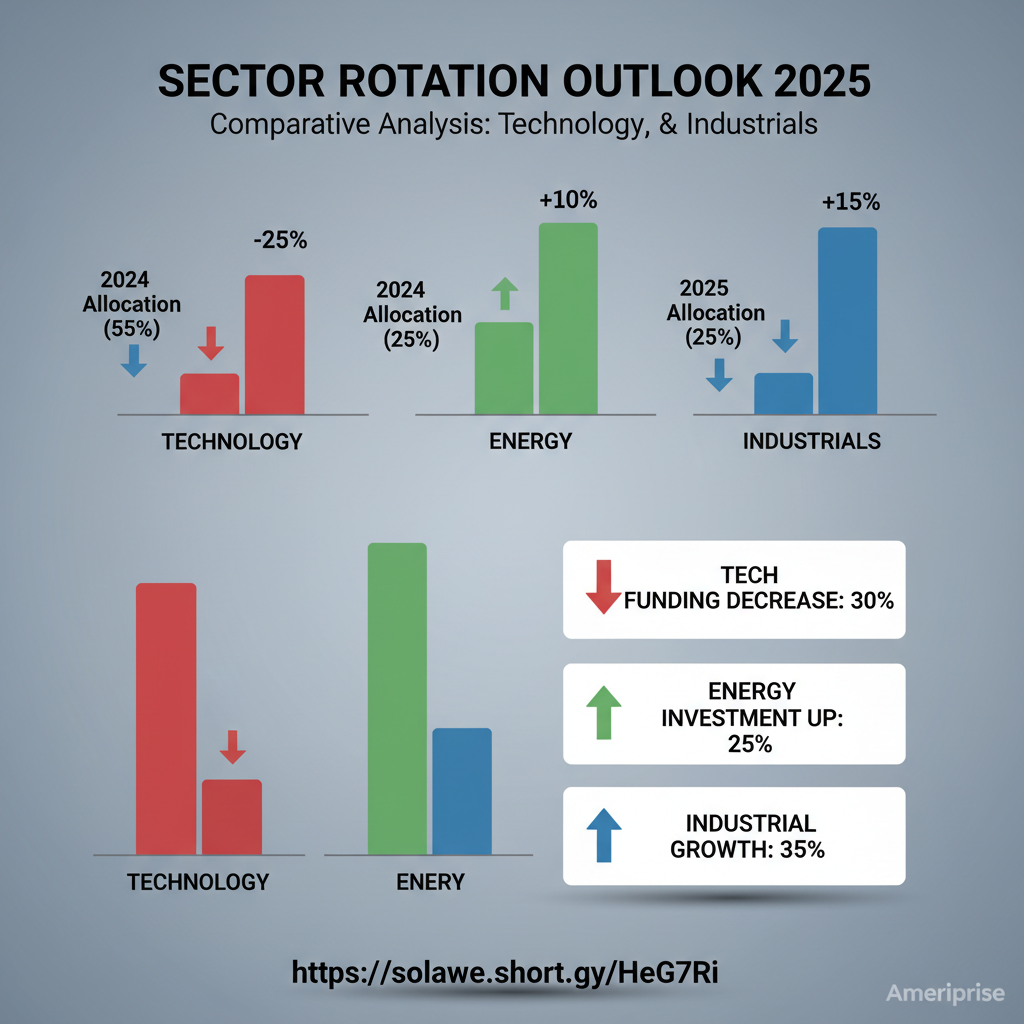

Cross-asset pricing confirms it. The CFTC’s latest Commitments of Traders report shows leveraged funds have slashed their net short position in 10-year Treasury futures to the smallest level since 2021. They’re not bullish on growth; they’re bullish on stability. Meanwhile, equity funds have seen $142 billion in inflows year-to-date through EPFR data, with a striking tilt toward late-cycle cyclicals—industrials, materials, energy. Tech still gets the headlines, but the money is moving down the risk curve into sectors that benefit from a high-rate plateau, not a low-rate fantasy.

The Rotation Is About Duration, Not Sentiment

This is where retail narrative and institutional reality diverge. The story you’ve heard is about AI fever and Mag 7 concentration. The story playing out in flow data is about duration positioning. When rates are volatile, investors shorten duration—sell long-dated bonds, shun growth stocks, hoard cash. When rates stabilize, even at elevated levels, they extend. But they extend selectively.

Energy is the tell. The sector has outperformed the S&P 500 by 1,200 basis points over the last six months, not because oil is screaming higher—WTI is stuck in a $75-$85 range—but because energy companies have become duration plays. They generate cash now, distribute it now, and don’t ask you to believe in a 2030 earnings story. In a world where the 10-year yields 4.6%, a 5% dividend yield from Exxon or Chevron isn’t just attractive; it’s rational.

Tech, by contrast, is experiencing a silent rotation beneath the surface. The Nasdaq 100 is up, but breadth is narrowing. CFTC data shows net speculative longs in Nasdaq futures have fallen 40% since January, even as the index made new highs. What’s happening is a quality culling: money is flowing into the megacaps that can fund AI capex through operating cash flow, and out of the dream stocks that still need cheap capital. The cost of capital isn’t coming back to zero. The market is finally acting like it believes that.

The BREIT redemption collapse fits this pattern perfectly. The investors who remained in the fund through 2024 weren’t the yield-chasing tourists; they were the ones who had already written down their mental account. They’d accepted the illiquidity premium as a sunk cost. When the Fed’s path clarified, they didn’t need to redeem to re-risk their portfolios—they could simply stop asking for their money back and let the duration play work. The gate became irrelevant because the psychology behind it had shifted from panic to patience.

The Reset in Valuation Sensitivity

What we’re witnessing is a wholesale repricing of how risk premiums are measured. For a decade, the risk-free rate was negligible, so every asset was priced on story, not spread. A private real estate fund could promise 6% yields and look attractive because 10-year Treasuries yielded 1.5%. The spread was wide, but the absolute yield was fiction.

Now the math is honest. A 5% yield on a private real estate fund needs to be compared to a 5% risk-free rate, plus a liquidity premium, plus a credit premium, plus an operational risk premium. That’s a much harder sell. But here’s the twist: once the adjustment is made, it’s done. The investors who stayed in BREIT have already accepted the new arithmetic. They’re no longer marking their positions to fantasy; they’re marking them to a new reality where 5% is the floor, not the ceiling.

This is why the redemption collapse matters for public markets. It signals that the great repricing of 2022-2024 is largely complete. The investors who couldn’t stomach the new regime have left; the ones who remain are building portfolios for it. CNBC’s talking heads keep asking if the market can rally with rates this high. The BREIT data suggests the market has already rallied by surviving the transition.

Consider the implications for sector rotation. If the risk-free rate is stable at 5%, then equity risk premiums don’t need to compress further for stocks to work. The S&P 500’s forward P/E of 20.5x looks rich against a 5% risk-free rate, but if earnings growth stabilizes at 6-7%—the current bottom-up consensus—then the equity premium is actually reasonable. More importantly, the dispersion within markets becomes the real opportunity. The megacaps trading at 30x aren’t pricing in rate cuts; they’re pricing in permanent dominance. The industrials trading at 15x with 4% dividend yields are pricing in permanent mediocrity. One of those assumptions is wrong.

The labor market data supports the more optimistic view, paradoxically. The BLS JOLTS report for February showed quits rates stabilizing at 2.3%, still above pre-pandemic levels but no longer falling. Job openings, at 8.9 million, are elevated but not bubbly. This is the fabled soft landing: enough slack to kill wage-price spirals, enough tightness to prevent demand collapse. For cyclicals, that’s goldilocks. For duration-sensitive assets, it’s permission to extend.

What does this mean for the individual investor trying to build a systematic framework? Stop looking for the old signals. The VIX at 14 isn’t complacency; it’s acceptance. The yield curve inversion that dominated 2023 has normalized, but not because recession is coming—it’s because the front end has repriced to reflect a higher neutral rate. The 2s10s spread at +45 basis points isn’t a green light; it’s a sign the market has moved on.

The real signal is in the flows that aren’t happening. The fact that BREIT’s gate is now moot tells you that private market illiquidity is no longer seen as a bug to flee, but a feature to price. The fact that energy is outperforming without a commodity bull market tells you that yield is the new growth. The fact that tech is rallying on narrowing breadth tells you that quality is being redefined as cash flow, not narrative.

This is the market’s new rhythm. It’s not about predicting the next Fed pivot; it’s about building portfolios that work whether cuts come or not. It’s not about timing the bottom in commercial real estate; it’s about accepting that the bottom is a process, not a moment. The investors who thrived in the 2010s were storytellers. The investors who will thrive in the late 2020s are accountants. They’re the ones who looked at BREIT’s 4.3% yield, compared it to a 5% risk-free rate, and decided to stay—not because they’re bullish on malls and office towers, but because they’re bullish on the end of uncertainty itself.

Wall Street’s best-kept secret isn’t that BREIT gated. It’s that the gating stopped mattering. The redemptions collapsed because the panic subsided, and the panic subsided because the math finally made sense. In a market addicted to drama, the most powerful move is to stop reacting and start accepting. The gate is still there. But everyone who wanted out has already left, and everyone who stayed has already made their peace. That’s not a crisis. That’s a clean slate.

For investors building frameworks in this new regime, the key isn’t chasing the next hot sector—it’s understanding how duration, liquidity, and risk premiums interact when the risk-free rate is no longer zero. Our quarterly strategy memo breaks down the cross-asset pricing models we’re using to position for a world where 5% is the floor, not the ceiling. Read the full analysis here.